Thursday 3 July had been predicted by Topmeteo and Skysight as a fantastic day – with best-in-year potential – well in advance, and so it was no surprise that a good crowd was already on the field, rigging, when I turned up around 8:10. In the spirit of incremental advances, I had planned on what to me seemed a pretty ambitious 670 km FAI triangle. Talking to Robert and Wendy, it became clear that perhaps something more aspirational should be attempted, a 750 km Yo-yo to Haye East, Bury St. Edmunds and Broadway. With my Mosquito prepared, including 50 litres of water, and waiting in the aerotow queue, I reconsidered this tricky question and went along with the majority choice to declare the 750 km Yo-yo. My determination wavered, when I realised that with an 11 am start, this would require 7.5 hours at 100 kph in my club-class glider so that I could return at a safe 6:30 pm. As it turned out, however, launch operations were very efficient and we got into the air and on task much earlier. This turned out to provide a much-needed buffer. A big thank-you goes to the club for making available two tugs and to the tug pilots, who got us all into the air promptly.

Setting out at 10:24 on the first leg, 200km to the Welsh border, things went very smoothly for a long time: climbs were moderate at 3-4 kts to 4,500 ft but reliable and tended to line up nicely along the westerly wind direction. Average speed was not high at about 73 kph, but this was against a 15 kph head wind, and for this time of the day, an effective 88 kph is pretty good. I mostly trailed behind Wendy in 700, who was a few hundred meters higher in thermals, so she would disappear on task when reaching the top, to be found again at the next climb, where she would very obligingly show the best lift.

About 20km from the first turn point, the strong conditions encountered so far turned into the more commonly encountered weather we endure on most days. In other words, it got pretty challenging. I suspect it had something to do with the hillier terrain, the stronger wind, and consequent dynamic effects (e.g. wave). Clouds were more like fleeting wisps of moisture, climbs were 2kts if at all and hard to centre. Wendy made a big detour to stay under good-looking clouds and stayed high. I, instead, made my usual mistake: being trapped in a hole. I detoured towards Shobdon in order to at least land out on an airfield if I had to, and dumped what little water my Mosquito can carry. On the way, I tried the western ridges of a few low, wooded hills, where I found bubbles of thermals, and gradually worked my way up by a few hundred feet – which gave the confidence to jump a gap towards a proper-looking cloud, where things were back to normal and I could now get around the turnpoint and back into the task.

The 250 km leg to Bury St. Edmunds went smoothly and fast, with an average of 118 kph (so >100 kph effectively, if you take away the tailwind component). How far could one go without having to thermal? A long way, under these conditions.

Turning back into wind at 3:20 pm after Bury, there were still 300 km to go on this task. I felt distinctly behind schedule, but I took comfort from the fact that a few days before, Mark Lawrence-Jones had started a 300 km out-and-return to Sheffield in our Perkoz not much earlier than this and under much more dubious conditions, and he got back just fine! Conditions in the East were indeed ballistic: while the climbs were never that outstanding, they tended to line up nicely and by now the cloud-base had crept up to 6,500 ft. Increasingly, it became important to route into areas that avoided 5,500 ft airspace.

Beyond Bedford, however, the situation got trickier, because clouds had now largely spread out, blocking out the sun and leaving large dead areas between the few sensible-looking cumulus. Approaching the final turn point seemed much more doubtful now, and there were some interesting discussions of our prospects on 130.130. Wendy, a little ahead, reported that she got a good climb in the sector of the last turn point, which motivated me to give it a go, gliding in from about 15 km away, where I had worked my way up to 5,500 ft under the last sensible looking cloud before the turn. One should approach upwind turns low, but after by now 7:30 h of flying, not just leisurely but constantly concentrating and pushing to make good speed, a field landing 120 km away from home is really not an appealing prospect: would I be focused enough to put the glider down safely and without damage? I approached this crucial part of the flight very conservatively. Trying some wisps on the way, I stumbled into a weak climb to gain 700 ft, then glid into the turn through dead air at 1 kt McCready and with the idea that Bidford or perhaps Edgehill would be good places to land in case this turned out to be the last thermal I’d find.

But hooray, there was indeed a good-looking cloud slightly upwind of the turn, with a fire on the ground appearing to feed it. Perhaps this was Wendy’s climb? It delivered and got me back to cloud base – the world now looked a lot more rosy.

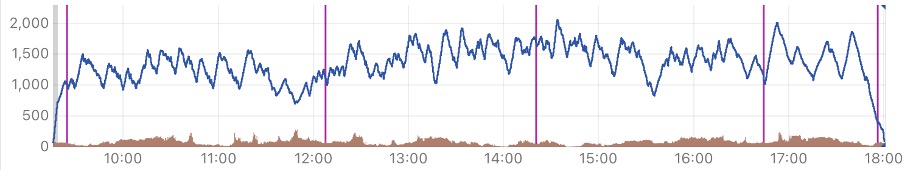

Looks like Duo-Discus 871 very small at the bottom edge of the picture

Andy and Mark in 871 and Graham in 841 had caught up at this point and entered the climb a good distance below. As I flew conservatively on the way back to Gransden, staying high and taking a 2kt climb to get almost onto glide near the HS2 construction project, they soon overtook me. It is reassuring to have experienced colleagues taking the lead when tracing out the way home in deteriorating conditions, I thought, swallowing the indignation. Or something to this effect, anyway.

It was now 8 hours into the flight, and the next decision could be crucial: the more direct route to Gransden seemed to be largely under spreadout, with little sun evident on the ground. A slight diversion to the North would get me into sunshine, where there were some healthy looking Cu. BUT, the best-looking Cu for miles was in a gap in the spreadout, directly overhead Milton Keynes. The northerly diversion seemed the safer choice, but I suspected that my gung-ho colleagues in 871 and 841 would go for the nicer-looking Cu that also required less of a diversion, and they would show the best climb, if indeed there was to be any. Seeing safety in numbers, I chose the more direct route, entered the climb at Milton Keynes (indeed marked by 871 and 841), and this clinched the flight. I got back to Gransden just before 7 pm, making this an 8 ¾ hour flight. The average speed was 88 kph, slower than I had calculated would be necessary, but just about fast enough.

Six hours in, I had begun to realise that this flight was going to be much tougher than I had expected: I have done fairly long tasks before, but this was on another level. You cannot afford to lose concentration and let your average speed slip – there just is very little buffer to absorb the time you lose in low points or weak climbs. But it is also a great adventure. I’d love to try it again soon.

– Malte