About a year ago, one of our professional instructors David Williams planted a seed in my brain – perhaps I should aim to become an instructor myself.

At that time, I considered myself still a relatively early glider pilot. I’d gained my license (“bronze & XC”, “SPL”), done a handful of cross-country flights, and was happily using our whole fleet of club gliders. But the furthest I’d been cross-country was about 100km. I was nothing like these sky gods who fly to York or Wales and back.

So, the suggestion took me a little by surprise: think about an instructor rating, already?

But there was no question that I wanted to do it — I love bringing friends and groups of people to the gliding club, and flying around with others was obviously my cup of tea, far more than doing solo cross-country epics myself.

For the year since that occasion, I’ve been pretty determined to pass this milestone, and thanks to the patience of my family and some tremendous instructor coaches, I’ve achieved it.

First a little on terminology. British gliding has three grades of instructor. The most basic is, unsurprisingly, “Basic Instructor” (universally called BI). That means (roughly) that we can take people flying for trial flights and instruct them on the primary effects of controls. Anything involving launches and landings requires a higher grade of instructor. Some say that being a BI is the sweet spot, because as the instructor, you still get to do a small amount of the flying yourself, at the beginning and end of the flight, which is of course fun!

Here’s how my journey unfolded.

Step one: talk to your dog.

Gliding instructors are supposed to use some exact phraseology when giving their lessons, which has been battle-tested to avoid confusing students. During your instructor training, you’re expected to use these exact words. Most importantly, you need to be able to use these words while flying the glider. So they need to be entirely automatic and involve no thought at all. I spent quite a bit of time practicing. My dog Remus now knows how to keep an excellent lookout, and any squirrels will be detected whether they’re above or below the horizon in any direction.

Step two: get the hours.

To start the Basic Instructor course, you need fifty hours of experience as pilot-in-command. To powered pilots, this sounds like no time at all. But, a lot of glider flights are five minutes long — fifty hours seemed like an insurmountable target. This was a particular problem for me because until this year, I mostly went flying during mornings when there are few thermals. At the beginning of 2025 I had hundreds of launches and landings, but only 24 hours as pilot-in-command. I gave it a fifty-fifty chance I could get to the magic 50 hours by the end of 2025.

Then April and May happened. We had an amazing spring for gliding, and some of the good weather happened to fall on weekends. I racked up the hours, including a five-hour flight. Thanks to my very supportive family for letting me disappear off to fly on many occasions.

I got to my magical 50 hours.

It is essential to have done some significant cross-country flights as part of this experience. Cross-country flights are all about workload management. You need to fly the aircraft, look out, navigate, talk to air traffic control, find thermals, stay in thermals, keep an eye on landing spots, drink water, and have a pee, all at the same time. It is an epic juggling task. Flying while talking is easy in comparison.

Step three: get coached!

Once it became clear that I actually was going to get the hours, I started to book sessions with our BI coaches, in order to get things ticked off on the Basic Instructor course record. We have tremendous BI coaches – instructor instructors, if you like. There really weren’t any surprises. I knew the phraseology, the workload was fine, and so it was mostly just a matter of ensuring that my general flying was up to the standard.

There were two areas where the coaching really improved things. First, although I had all the phrasing of the exercises down pat, I needed to co-ordinate my speech more perfectly with the demonstrations. Specifically, explain what I’m about to do, wait a second for it to sink into the student’s brain, then do it. Rather than doing it at the same time as speaking.

Secondly, planning a route. Obviously, the student will be turning the aircraft. How do you ensure that the student can turn any way they want yet you’re always in the right position to do the next exercise and get back to the airfield? This is not due to some secret instructor chip controlling the free will of the student (honest). It’s just a matter of learning the correct amount of nudges to give.

Towards the end of my coaching, I needed to do the dreaded stalling and spinning sessions. I have an unusually pathetic stomach and I knew this would be horrible. It was. The less said about this the better, except to note that I didn’t actually throw up. Victory.

Our simulator was a great tool for a lot of this stuff. Practicing recovery from failure conditions is much quicker and more efficient when you don’t need to drag a glider all the way up the airfield each time.

Step four: flight exams.

After all the coaching, our Chief Flying Instructor spent an afternoon flying with me to ensure all the coaches had made good judgments about my suitability. This step of the process was a bit opaque in advance, but it was really just a re-run of much of the rest of the course, especially focused on recovery from failure conditions, and on generally running a flight with a fake student. Fortunately no more stalling and spinning.

Step five: paperwork.

Step six: do it!

Finally, the big day arrived, when I got to fly with my first students. That day was yesterday!

We had an evening event planned for a lot of colleagues from my former employer.

Was I nervous? Mostly no. I was just very excited!

I was a little nervous about the intensive operations required for an evening flying event. Flights are short in evening events (a great taste of gliding, but not much more than that) and precision is required around timings and landings in order to keep the operation running efficiently and smoothly. Was I sure I could land on the correct spot on the runway to avoid disrupting launches, each time? Was I sure that I could give every student the right information in the ground briefing without taking too long and delaying the next launch? If I was inefficient, we might not get all of our guests into the air. Quite a challenge for a brand new instructor.

So, I wanted to do some long daytime aerotow flights first. Fortunately, a friend from my village, together with two of the evening attendees, wanted to come along to fly in the afternoon. Thanks to other instructors’ flexibility, I managed to claim a glider and we went flying!

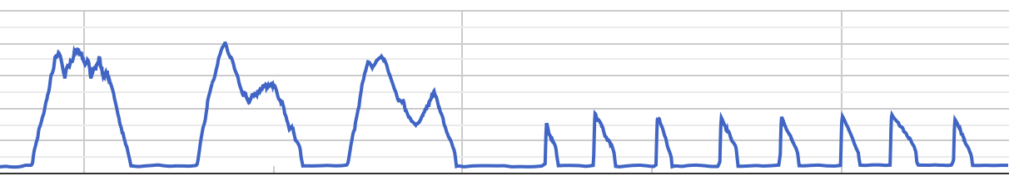

I had three absolutely delightful aerotow flights, each of 30-35 minutes. In each of them, we found some lift (you can see from the altitude trace below). We’re advised not to spend too long circling in thermals with new pilots, because it can make people queasy, but all three of my friends had very strong stomachs and were happy to do some circling around to gain height.

Those were some of the most enjoyable flights I’ve had. It was great!

I was delighted to tell Vanessa, my first student, that not only was it her first time gliding but it was my first time instructing. And we both had an absolutely lovely flight (she was great!)

After the three aerotow flights, I went straight into the evening session with eight winch launch flights. They were also good fun. As expected, much shorter and more intensive, with less time for the students to fly the aircraft — but a great introduction to gliding and it was lovely to fly with so many people.

So, was it all worth it? Would I recommend becoming a Basic Instructor!

100%! I can’t overemphasise how much I loved every moment of yesterday. Flying around with new pilots was everything I’d hoped it would be. It was a cheat code for doing lots of flying. Eleven launches and landings in half a day! But above all it was absolutely lovely being there while new pilots discovered that yes, they actually could fly an aircraft and yes, thermals do work to keep you aloft even without an engine. It’s a massive privilege being there while these discoveries occur. Thanks to all my students, instructor coaches, and to David who suggested all this a year ago!

If you’re a qualified glider pilot considering becoming a BI — and you’re a sociable person — do it! And if you’re not yet, come along to the club and start your journey.